I was ordained in my home church, Union Congregational Church UCC in Rockville, Connecticut, thirty-six years ago today.

A lot of things have changed in the intervening three and six-tenths decades. For one thing, my home congregation left the United Church of Christ, which is a lingering ache. My father retired from a distinguished career as a public school educator, completed a seminary degree, and was ordained himself. My daughter has also graduated from seminary and I look forward to celebrating her ordination. My son has kept his concentration on the writing and creating he wants to do, a quest that has taken him to the heartland of Arthurian stories in Wales.

The UCC has lost members and lost churches every one of these thirty-six years. We’re not alone. Similar things have happened in “mainline” Protestant denominations and in traditions that have rejected the mainline. The church has aged. Even now, as I have entered my sixth decade, I remain younger than a majority of my parishioners.

It seems like I ought to have learned something over all these years, and to have some wisdom to offer to colleagues, friends, church members, and church leaders. I feel like I should. If I do, I wish it were clearer to me.

The time has passed in the blink of an eye, a blink of an eye that has included innumerable endless days.

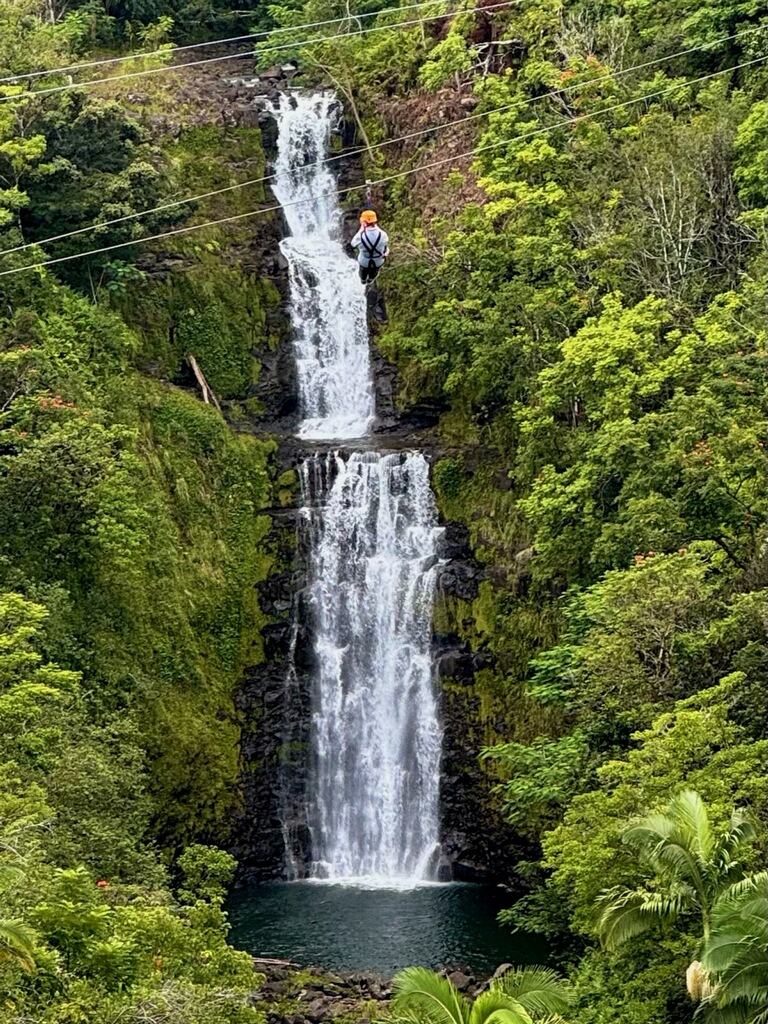

A couple weeks ago ministers of the Hawai’i Conference gathered for a retreat, which was held just a few miles from my home. On one of the afternoons, we participants could participate in “adventures.” For various reasons, including the vigorous advocacy of a young person in my congregation, I was asked to be the local pastor who accompanied (and joined) those who took part in a zipline adventure.

It wasn’t entirely outside my wheelhouse. While in Connecticut, I sought training as a ropes challenge course facilitator. I really enjoyed the training and the work of guiding people through an experience of testing their boundaries, trying something scary and finding a new sense of accomplishment. As I’ve put it more than once, facilitators spend their time safely on the ground, but in training we spent more time at the heights. The conference’s retreat center didn’t have a zipline, but I did get a chance to try one before moving to Hawai’i.

The simple truth is that I don’t have much fear of heights, and doing that training and that work taught me to trust the equipment.

I still wasn’t sure how I’d feel until I set off on the first zipline that afternoon. Would it be exhilaration? Had I developed a fear of heights without realizing it? Would something else happen that I didn’t anticipate?

It did. I settled into the harness, glided along the cable, and felt about as relaxed as I’ve felt in some time.

Yes. You read that right. I felt relaxed.

I was surprised, too.

Relaxation can be hard to come by in a pastor’s life. Sometimes pastoral duties come with a lot of anxious energy. The other day I received an urgent call to go to the hospital, as someone from another church, someone I have known and worked with, had been rushed there by ambulance. When I got there, nobody had a record. It turns out that they’d died in the ambulance without ever reaching the hospital.

That afternoon brought a lot of concern, anxiety, shock, and grief.

If I have any wisdom to offer on the thirty-sixth anniversary of my ordination, it’s this: Relax into the glide of the zipline. Ministry can feel like an uncontrolled glide over a yawning chasm at times: mercifully, not all the times. When it does, the mechanisms that keep me from falling aren’t readily apparent, or if they are, I may not be convinced of their strength. Those pitfalls look awfully deep.

Relax into the glide.

You’ll get to the other side.

It’s an imperfect metaphor, of course. One of the features of ziplines is that they make straight lines between one place and another. Ministry frequently doesn’t. You set off in one direction, and find yourself landing in a completely different place. Thirty-seven years ago, did I expect that I’d do interim ministry? Play the guitar and ukulele? Manage IT and publications for a Conference? Facilitate on a challenge course? Pastor a church in Hawai’i?

No, no, no, no, and no.

Not all of my transitions have been gentle (far from it) and not all of my landings have been soft (far from that, too). The ground that looked firm has crumbled beneath my feet both at the beginning and the end of the traverse. I still don’t really understand the systems that have kept from out of the crevasse all these times.

But if I have one piece of advice, it is: Relax into the glide.

You’ll get to the other side.

The photo shows me (a gray figure with an orange helmet) gliding down a zipline over a waterfall. Photo by Ben Sheets.